Tuesday, December 2, 2014

Warhol's Jackie The Week that Was

Sunday, November 30, 2014

Robert Rauschenberg's Bed

Robert Rauschenberg's 1955 Bed is an example of what he called a "combine," a work of art that melds painting, sculpture, and collage. Rauschenberg was inspired both by the Cubist innovation of collage as a means to bring the materials of everyday life into works of art, and by the gestural painting techniques of Jackson Pollock, which you already discussed in section and which we will be addressing at greater length in lecture of Tuesday. What kinds of implications does Rauschenberg's Bed suggest to you? What does it mean to take a intimate object like a bed (where one sleeps, makes love, etc.) and to hang it vertically on the wall of an art museum? How is Rauschenberg's approach to both collage and painting similar or different from Picasso's and Pollock's?

Sunday, November 23, 2014

Salvador Dali's Phenomenon of Ecstasy

Salvador Dali's 1933 "Phenomenon of Ecstasy" is a photomontage, or collage of photographs, that represents how artists who were part of the Surrealist movement adapted photography and collage (both still relatively new media) to their interest in exploring unconscious states of mind, dreams, fantasies, etc. Surrealists sought out new artistic processes as a means both to excavate and represent a new understanding of the human mind inspired by the psychoanalytic studies of Lucien Freud. At the same time that Dali is interested in unconscious phenomena, however, he is also looking back to an interest in expression and emotion evident already in classical sculpture and seventeenth-century Baroque works like those of Bernini. How might you compare and contrast Dali's interest in the ecstatic body to Bernini's sculptures "Ecstasy of St. Teresa" or "Pluto and Prosperina?" And why do you think he focuses here almost exclusively on female subjects... or does he?

Wednesday, November 19, 2014

Picasso's Absinthe Drinker and Glass of Absinthe

The Spanish artist and pioneer of Modernism Pablo Picasso, in his painting of an "Absinthe Drinker" from 1901, reflects the culture surrounding this highly intoxicating spirit. Absinthe was thought at the time to have hallucinatory effects and was popular in France already in the nineteenth century. The woman holds a sugar cube in her hand, which was used in the drink's preparation. Once the absinthe was poured in a glass, a sugar cube was placed atop a slotted spoon and dissolved by cold water poured on top of it, creating a milky effect in the drink itself. Over a decade later, Picasso returned the subject in a small sculpture "Glass of Absinthe" from 1914 (21.6 x 16.4 x 8.5 cm), which is created from painted bronze. What has changed in Picasso's approach to the subject matter of absinthe drinking between his 1901 painting and the 1914 sculpture? To what extent is the sculpture "representational," in other words, to what extent does it actually depict something as one would see it in the real world? Or does it seem instead to do something else?

Sunday, November 16, 2014

Thomas Edison's Brooklyn Bridge

Thomas Edison's short film from 1899 "New Brooklyn to New York via Brooklyn Bridge, no. 2" represents both the nature of early cinematic production, before the advent of narrative film, and an interest in the modern city that we began to trace last week in our discussion of nineteenth-century Paris. In this two-minute clip of a train crossing Brooklyn Bridge, what does the filmmaker seem interested in capturing for his audience? How does the film figure the city of New York in a way similar or different from the representations of industrialization and growth apparent in the works of the Impressionists? And how might we understand Brooklyn Bridge as a modern counterpart to the Gothic cathedral?

Tuesday, November 11, 2014

Van Gogh's Pair of Shoes

Vincent van Gogh made several paintings of shoes, including this work from 1885, which sparked an exceptional debate among twentieth-century art historians and philosophers including Martin Heidegger and Jacques Derrida. You might ask how a painting of a pair of shoes could generate so much discussion? That such a debate came about raises the question of what Van Gogh was after in making a painting of boots in the first place. Is this just a random still-life of what happened to be laying around Van Gogh's studio, or do these shoes bring up particular associations for you? And is there any implication in your mind of the individual (or social category of person) to whom these shoes belong? What significance do you see in the details Van Gogh chooses to emphasize and in the way he handles the paint itself (brushstrokes, thinness/thickness of paint, etc.)?

Sunday, November 9, 2014

Mary Cassatt's Interior of a Tramway Crossing a Bridge

Mary Cassatt was a nineteenth-century American painter and printmaker who made her career in France as one of the foremost female Impressionist artists. Her work is often described as characteristically "feminine" in her focus on representing women, girls, and mothers in intimate, soft interiors. In this print, however, Cassatt addresses a new phenomenon of modernity: the working woman out in public. Riding in a tramcar (itself a modern innovation) are a working woman dressed in a high-collared dress and a nursemaid holding her baby. Cassatt combines the media of drypoint etching and aquatint in creating this remarkably stark image. What strikes you as significant about the details that Cassatt chooses to include in this print, and what do you imagine we are meant to understand about the sentiments and relationship between the figures represented?

Tuesday, November 4, 2014

Goya's Portrait of Manuel de Zuñiga

Thursday's lecture will focus on the great eighteenth-century Spanish artist Francisco Goya, whose works might superficially seem to belong under the rubric of "Romanticism," but whose art is in actuality much more singular. One genre in which Goya excelled and found eager patronage was that of portraiture, of which this strange painting of Manuel Osorio Manrique de Zuñiga (1787-88) is a particularly unusual example. Manuel was the son of the Count and Countess of Altamira and is dressed as befitting his noble status in a splendid red costume. Yet Goya also surrounds the child with animals, including the magpie at Manuel's feet who is depicted holding Goya's own calling card in its beak. We have talked already in class about the role of signatures in works of art like Bruegel's Big Fish Eat Little Fish engraving, and about experiments with the genre of portraiture as exemplified by Rembrandt's contributions to the genre. In some past scholarship, Goya's portrait of Manuel has been interpreted according to traditions of animal symbolism, in which caged birds embody childhood innocence and magpies signify gossip, but as we will discuss in class, these interpretations do not prove wholly satisfying. What details or aspects of this portrait seem significant to you in terms of understanding both how Goya intends to represent Manuel, and how Goya situates himself (through his calling card) in relation to his artistic creation?

Sunday, November 2, 2014

Fuseli's Nightmare

Our topic for Tuesday's class will be the tension between the movements of Neoclassicism and Romanticism in art produced during the latter half of the eighteenth century. While Neoclassicism concerned itself with the formal revival of Greco-Roman figures and architectural models, Romanticism was motivated by more emotional and subjective impulses, and often inspired by contemporary theatre and literary genres like poetry and horror novels. The Swiss artist Henry Fuseli (1741-1825) exemplifies the romantic approach both in his manner of painting and choice of subjects, including this famous painting titled The Nightmare. How does Fuseli's approach to the subject of the female body, and his implication of the viewer's presence, differ from that of Francois Boucher in his Lady on a Her Day Bed or from other works we have seen thus far in class? Is Fuseli's woman self-absorbed in the manner of Boucher's women, or is something else going on here?

Tuesday, October 28, 2014

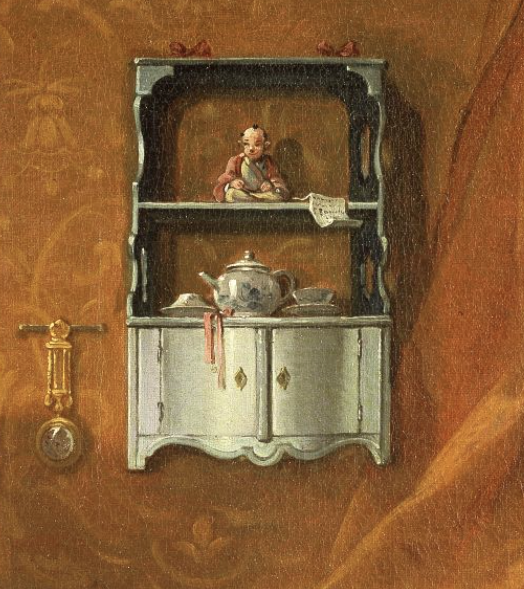

Boucher's Lady on her Day Bed

Francois Boucher was one of the leading artists in eighteenth-century France, who created not only paintings but also designs for prints, tapestries, and porcelain. This small image, for which Boucher's wife posed as a model, might seem almost frivolous compared to the grand historical and religious narrative paintings we have seen in class thus far. There is no ostensible story, and although it represents a specific individual (and thus overlaps with the genre of portraiture), there is as much emphasis on the stuff in the composition (like the objects displayed on the back wall) as on the figure herself. Does this picture seem casual or posed, or a combination of the two? Why do you say so? Is it possible there there is no "point" to the painting beyond being a pleasant representation of Madame Boucher, or do any details seem to indicate an underlying message?

Sunday, October 26, 2014

Rembrandt's Self-Portrait in his Studio

At the end of class this past Thursday, we looked at Velazquez's monumental painting "Las Meninas" (3.2 x 2.7 m), which includes among many other figures a self-portrait of the artist at his easel. This painting by the young Rembrandt is by contrast very small (just 24.8 x 31.7 cm), yet it still makes a provocative claim about its maker. Considering the question of how artists participate in the construction of their own myths and fame, as per our section discussions last week, how would you describe Rembrandt's compositional choices and self-presentation in this painting as similar to and/or different from that of Velazquez?

Wednesday, October 22, 2014

Caravaggio's Conversion of Saint Paul and Bernini's Saint Longinus

This Thursday we will be discussing early seventeenth-century art in the context of the Counter-Reformation, the movement on the part of the Catholic church to revive religious art in the face of the Protestant attacks fomented by Martin Luther a century earlier. Two artists in Italy, Caravaggio and Bernini -- in the media of painting and sculpture respectively -- exemplify the kinds of religious artworks created in this new Counter-Reformation context, as well as a new dramatic approach to representing narrative. Comparing Caravaggio's painting of "The Conversion of Saint Paul" blinded by the light of God and fallen beneath his horse with Bernini's sculpture of "Saint Longinus" in the choir of St. Peter's in the Vatican, what do you notice to be common features and approaches in both artists' works? You might compare/contrast the portrayal of the body, gesture, and the use of light, as well as the different media used by the artists.

Saint Paul's conversion, from Acts 9:1-6 (note that Saint Paul's original name was Saul):

Meanwhile, Saul was still breathing out murderous threats

against the Lord’s disciples. He went to the high priest and

asked him for letters to the synagogues in Damascus, so that if he found

any there who belonged to the Way [i.e. Christian believers], whether men or women, he might take

them as prisoners to Jerusalem. As he neared Damascus on his journey,

suddenly a light from heaven flashed around him. He fell to the ground and

heard a voice say to him, “Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me?”

“Who

are you, Lord?” Saul asked. “I am Christ, whom you are persecuting,” he

replied. “Now get up and go into the city, and you will be

told what you must do.”

Sunday, October 19, 2014

Bruegel's Big Fish Eat Little Fish

Tuesday's lecture will focus on the impact of the Protestant Reformation, the radical break with the Catholic church fomented by the German preacher Martin Luther beginning in 1517, which comprised among many things a strong critique of perceived decadence and idolatry in Catholic religious images. One practical result of the Reformation was the emergence of new genres of art that were not religious in subject matter, but comprised the representation of scenes from everyday life and popular culture. A particularly remarkable example is this engraving by the Netherlandish artist Pieter Bruegel the Elder (published 1557), which illustrates the popular Dutch proverb "big fish eat little fish," a comment on the hierarchical man-eat-man (or fish-eat-fish) world of human society. Remarkably, the print is not signed in the bottom left corner with Bruegel's own name but instead with the phrase "Hieronymus Bosch inventor," which would suggest that Bosch and not Bruegel designed it, even though this is not the case! What connection do you see between Bruegel's "Big Fish" print and Bosch's works that we discussed earlier in the semester, which might justify the reference to Bruegel's artistic precursor? And what you think might be possible explanations for why Bruegel and/or the publisher of this print used Bosch's name instead of Bruegel's?

To compare Bruegel's engraving with his preliminary drawing for the print in close detail, see this website:

http://80.57.84.48/Albertina/

Monday, October 13, 2014

Raphael's Stanza della Segnatura and Thomas Struth's 1990 photograph "Stanze di Raffaello II"

The contemporary photographer Thomas Struth created a celebrated series of images depicting visitors in front famous works of art and in popular museums like the Louvre in France. Here he photographs tourists in Raphael's great Stanza della Segnatura in the Vatican Palace in Rome, part of the papal apartments that the young artist frescoed in 1508-09 for Pope Julius II, and which includes one of the most well-known images from Renaissance art, the "School of Athens." At the center of Raphael's fresco, the ancient philosophers Plato and Aristotle stand framed by an arcade while a group of other celebrated thinkers and creators spread out around them. Looking at Struth's photograph, it is clear that he is asking us to think about the extent to which tourists really engage with the works they travel to see. Raphael's "School of Athens" is not visible in Struth's photograph but is on the wall to the left of the crowd. How might Struth be commenting on Raphael's fresco through his photograph? Do you think he means the viewer to compare/contrast the photographed scene with Raphael's fresco? Are there similarities between the two compositions that invite this comparison, and what might we understand from the juxtaposition?

Tuesday, September 30, 2014

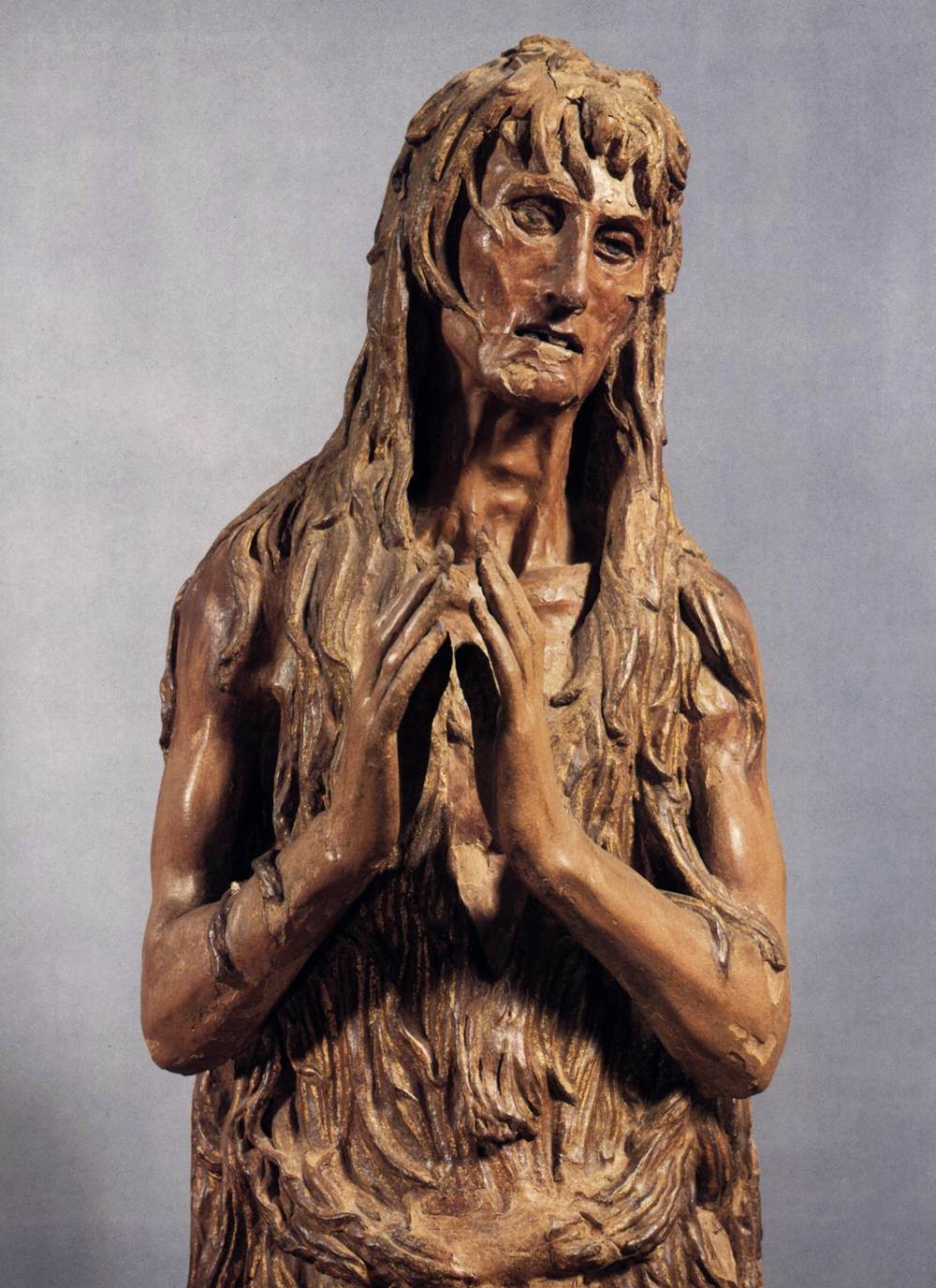

Donatello's Mary Magdalene

This Thursday we will be discussing the early Italian Renaissance in Florence, which is in many ways a counterpart to Bruges (the hometown of Jan van Eyck) in northern Europe. Yet unlike in Bruges, it was sculpture rather than painting that dominated the achievements of Florentine art during the fifteenth century. The sculptor Donatello was one of the greatest artists in the city who produced several works, likely including this wooden statue of Mary Magdalene, for the Florence Cathedral. Mary Magdalene was a prostitute who converted to Christianity and became a follower of Christ. According to legend, she became an extreme penitent after Christ's death, living in the wilderness and devoting herself to prayer. Donatello depicts her here during this period at the end of her life. The sculpture would originally have been fully painted and was even partially gilded with gold leaf. How does Donatello use details such as texture, pose, etc. to heighten the drama of Magdalene's figure and emphasize her piety? Does anything surprise you about this work as an example of Italian Renaissance art, based on your prior knowledge and expectations?

Sunday, September 28, 2014

Hieronymus Bosch's Death and the Miser

Tuesday, September 23, 2014

Rogier van der Weyden's Descent from the Cross

Sunday, September 21, 2014

Giotto's Lamentation of Christ

This week we begin our discussion of the Early Renaissance period, which raises a key question: to what extent does the Renaissance constitute a break from the past and to what extent does it continue the interests, themes, and functions of art established in antiquity and the Middle Ages? Giotto's frescoes for the Arena Chapel in Padua (c. 1305) are an excellent case study for this question. Look closely at this scene representing the Lamentation of the Dead Christ by the Virgin Mary and his other followers. Do any aspects of the scene (its structure, emotion, etc.) remind you of other works we have discussed already in class? What figures in particular stand out to you for their poses and expressive qualities?

Tuesday, September 16, 2014

Chalice of the Abbot Suger of Saint-Denis

In your textbook (Janson, p. 393), there is an excerpt from the very famous description written by the twelfth-century Abbot Suger describing his rebuilding of the French royal Abbey Church of Saint-Denis ( 1137-1144 CE). Suger addresses one of the questions that came up in Tuesday's lecture: what is the justification for the creation of costly treasury objects in Christian churches? If the Christianity understands God as an invisible presence, why the emphasis on shiny visible and material things?

Suger says the following (and by "we" he really means "I"):

"We insisted that the sacred, life-giving cross should be adorned. Therefore we searched around everywhere by ourselves and by our agents for an abundance of precious pearls and gems... Often we contemplate these different ornaments both new and old. When the loveliness of the many-colored gems has called me away from external cares, and worthy meditation has induced me to reflect on the diversity of the sacred virtues, transferring that which is material to that which is immaterial: then it seems to me that I see myself dwelling, as it were, in some strange region of the universe which neither exists entirely in the slime of the earth nor entirely in the purity of Heaven; and that, by the grace of God, I can be transported from this inferior to that higher world..."

The chalice pictured above was part of Abbot Suger's treasury and was used in the ceremony of the Eucharist during the Christian Mass, and ceremonial celebration of Christ's body and blood. The chalice would have been used for administering the wine that symbolized the blood of Christ. Like the Lothar Cross, it combines an ancient Roman stone cup and inset gemstones with a medieval gold setting. What is Suger's justification for creating precious objects like this chalice, and what might be the argument against his claims?

Sunday, September 14, 2014

The Bronze Doors of Bishop Bernward, Hildesheim Cathedral

The bronze doors commissioned by Bishop Bernward for Hildesheim Cathedral in Germany, and completed in 1015, are one of the most seminal works of early Medieval art. They represent an interest in reviving the art of bronze sculpture from antiquity, which we saw already in class as practiced in the ancient Near East and Etruria. They also demonstrate the continued interest in the medium of relief sculpture as a means of conveying narrative (which we have seen in the Parthenon metopes and the Arch of Titus in Rome). The small vignette here shows the angel expelling Adam and Eve from Paradise after they have eaten the forbidden fruit and committed Original Sin. How do the representation of figures and choice of details included in this sparse composition convey that story? You might also comment on how this relief sculpture differs from the narrative movement and drama of the Arch of Titus frieze we discussed last week.

Tuesday, September 9, 2014

The Maison Carrée in Nîmes, France

The Maison Carrée in Nîmes, France (top image) is one of the best preserved of all ancient Roman temples. Significantly, it is NOT in Rome but was erected in the Roman province of Gaul (as the region of France was known in antiquity). Art and architecture in the provinces was one means for the Romans to assert their authority through visual presence, even at great distance from the ancient capital.

When the American president Thomas Jefferson traveled through France in 1787, he visited the Maison Carrée and declared that it was "the most perfect and precious remains of antiquity." When he returned home, he also modeled his architectural design for the Virginia State Capitol (bottom image) in Richmond on the Maison Carrée. Interestingly, Jefferson never visited Rome and so his appreciation for the temple in Nîmes may have been inflected in part by his lack of firsthand knowledge of more famous Roman buildings. Yet even so, why do you think Jefferson might have found the Maison Carrée so appealing and how did he adapt its model in his design for the Virginia Capitol (i.e. what is similar and different between the buildings)? And what do you notice about how the Maison Carrée itself differs from the design of the ancient Greek Parthenon?

Sunday, September 7, 2014

Etruscan Tomb from Cerveteri

Across the history of art, representations of smiling figures prove to be far less common than serious expressions. In difference to our modern inclination to smile for the camera, artists and patrons in antiquity and pre-modern Europe most often opted for portrayals that emphasized intellectual, political, or religious authority through features variously stern, pensive, and commanding. The ancient Archaic period, however, was a notable exception to this general tendency, and this ancient Etruscan funerary sculpture pictured here is one of the most famous examples of smiling in Western Art. Designed to serve as part of the couple's burial complex, the sculpture shows the pair not only alive but also actively engaged with one another as they recline on a bed. Some questions to consider: How would you describe the expressions on their faces? How are they portrayed differently from the sculptures of Egyptian ruling couples that we discussed last week? And what features of the two figures seems especially significant/interesting to you?

Wednesday, September 3, 2014

Isadora Duncan and Jane Mansfield at the Parthenon, Athens

These two old photographs show the famous dancer Isadora Duncan (top) and actress Jane Mansfield (bottom) standing in the ruins of the Parthenon, the most celebrated monument of ancient Athens. We will discuss this monument in detail during this coming Thursday's class. As a preview to our discussion, these photographs raise an important question: what is the relationship between the body and architectural space? How do these two images comment on that relationship and consequently emphasize different views/interpretations of the ancient structure itself?

Sunday, August 31, 2014

Bust of Queen Nerfertiti

Last week, we already encountered several kinds of sculpture (Venus of Willendorf, Head of an Akkadian Ruler) and the different potential functions that three-dimensional art objects might play. This ancient Egyptian bust of Queen Nefertiti offers a new category of sculpture: the portrait bust. This portrait head carved from limestone, and completely in the round, was kept as a model in the artist's studio for the creation of standard likenesses of the ruler. Nerfertiti served as priestess in the new religion established under her husband's rule and thus has exceptional prominence in the history of Egyptian queens, which perhaps motivated a greater demand for portraits representing her. The right eye of this bust was never completed with inlay crystal and a painted pupil, likely because this was a model and not a finished work. We will discuss more background on Queen Nerfertiti in class, but based simply on these images, what would you see makes this work a portrait? What details of the bust indicate that she is an individual and not just an ideal type, or do you think it is some combination of the two?

And just for fun, here is a clever and humorous take on the difference between Egyptian and Greek approaches to representing the body (sent to me by one of your classmates):

Tuesday, August 26, 2014

The Woman of Willendorf

The small statue known as the "Woman of Willendorf" was created ca. 28,000-25,000 BCE. Because we have no idea about the function of this statuette or precisely what it was meant to represent, it is easy to project our own conceptions of the body onto its form, as the funny cut-out sheet of outfits shown here demonstrates. Yet even if we don't know much if anything about its history, we can still consider it as an object. According to your reading in Janson, we might be able to see the beginnings of an interest of abstraction in the figure. How would you argue for or against this understanding of the sculpture as "abstract" beyond what Janson suggests?

NOTE: some of you may have been introduced to this work previously under the title "The Venus of Willendorf" (the title that appears in the still cut-out outfit image above). Discoverers of this sculpture first associated her with the ancient goddess Venus because of the emphasis on the fertile body, but it is anachronistic and somewhat misleading to do so. Venus was a goddess of Greco-Roman antiquity and was not a part of Paleolithic culture! That is why we now call her simply "Woman of Willendorf."

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)